—for climate adaptation

Communities need to become more resilient in the face of climate change. And the problem is only increasing.

There were six-times more billion-dollar severe storms during 2001–2022 (142 events) than the prior two decades (25 events/1980–2000) and the average cost of those billion-dollar storms rose from $2.5 billion (1980–2000) to $15.4 billion (2001–2022). Rainfall rates are likely increase with studies modeling 10-15% increase in rainfall rates within 100 km of the storm under a 2˚C warming scenario. It’s also getting much hotter in many places with summers becoming almost unbearable. This has impacts for public health as well as for wildlife, birds and amphibians. Plant communities also change and in some case food sources are available at the wrong times of the year for animals, birds or insects that depend on them. Helping communities adapt and become more resilient is a key area of practice at GIC.

What is “ecosystem resiliency”?

Resilience is the capacity of an ecosystem to respond to a disturbance by resisting damage and recovering quickly. Disturbances can include such events as extreme fires, flooding, hurricanes or tornadoes – as well as human activities such as converting natural landscapes to developed uses, fracking for oil, or introducing exotic plant or animal species. These activities affect ecological resilience by over-exploiting natural resources, polluting the ecosystem or reducing biodiversity. When a community is resilient it can recover – bounce back – more easily from such disturbances.

What is social resiliency?

Resiliency is a term that is also applied to human communities. Places with greater social cohesion, cooperation and support for community engagement are indicators of a resilient community. When social resiliency is low it can be rebuilt by re-networking isolated places, building community knowledge and empowering disadvantaged communities with tools to have their voices heard.

The key is to build both ecological and social resiliency. For example, restoring natural shorelines in developed areas or clearing debris after a fire and engaging the community in such work builds both types of resiliency! Social equity is also key. Plans should ensure that the most vulnerable communities are protected from harm – regardless of race or income. Efforts to address flooding or to green a community should be available to everyone.

The key is to build both ecological and social resiliency. For example, restoring natural shorelines in developed areas or clearing debris after a fire and engaging the community in such work builds both types of resiliency! Social equity is also key. Plans should ensure that the most vulnerable communities are protected from harm – regardless of race or income. Efforts to address flooding or to green a community should be available to everyone.

So, improving resiliency includes improving habitats for species diversity, monitoring and removing invasive species, reducing pollution, protecting natural landscapes, mitigating against extreme fire and flooding, storm and emergency planning and so on.

GIC can help communities become more resilient by:

- Identifying sensitive ecosystems and threats to their stability

- Creating strategies to reduce threats

- Rebuilding ecosystems and communities through actions such as replanting corridors or restoring native shorelines

- Helping communities prepare for storms and flooding, respond appropriately and recover quickly.

Resiliency Planning

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk, Virginia

GIC assessed and mapped the city’s green infrastructure and created strategies for making the City of Norfolk more resilient to a changing climate. The plan evaluated both current green infrastructure (trees, water, wetlands and other habitats) and marsh- and forest-buffer migration as sea level rises. We are now working on a similar project in Hampton, VA Download the report here.

Resilient Coastal Forests

Resilient Coastal Forests

In GIC’s Resilient Coastal Forests Project, conducted with Virginia, South Carolina and Georgia, we studied the benefits of coastal forests and the many unique and interacting threats – climate change, pests and diseases, development – to address for a sustainable future. To learn more see our Resilient Coastal Forests Project Page.

Trees and Stormwater

Trees and Stormwater

In GIC’s Trees and Stormwater Project we studied the role of trees in taking up stormwater. Climate change, extreme weather and development have led to many cities and towns losing significant tree cover — 30,40, or 50% or more — leading to more flooding (no trees to evapotranspire water) and hotter days (no shade trees). GIC developed a model to take mapped trees and translate that into gallons of water absorbed and also pollution prevented – the nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment that trees intercept which protects surface water quality. We also looked at urban heating and developed studies of how trees can make cities cooler. To learn more, visit our Trees and Stormwater page.

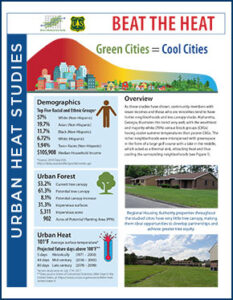

Extreme Heat Studies

Extreme Heat Studies

Storms are becoming worse, and some of that is because of extreme heating. As the oceans heat up, more water is available to the atmosphere, leading to more extreme storm events. Extreme heat in cities even causes microclimates where it rains more due to excessive evaporation into the atmosphere. GIC studied heating in 13 communities and released a series of reports and developed tools to show how planting trees could be used to reduce future temperature increases and save on energy use too. See GIC’s Green Cities page for more on urban canopy planting. You can view the individual 13 Community Urban Heat Reports here.

Storm Planning and Recovery

Storm Planning and Recovery

GIC helps communities get the right tools in place to prepare for, manage and recover their urban forests from storms. Pre-contracting ensures that support is ready to respond quickly with personnel who are FEMA-qualified and can get streets and facilities re-opened by removing risky trees or branches and blocking debris without harming vegetation that isn’t a risk. Managing debris right and replanting following disasters – hurricanes, tornadoes, floods or earthquakes – will ensure community safety immediately and restore ecosystem functions after the disaster ends. Monitoring trees to check for risk – Tree Risk Assessment – can save time, money and lives by removing trees that could fail and cause harm or block access. To learn more, download our resources below and visit our Storm Mitigation Planning page.

Find more Storm Planning reports and books in our Resources section here: Storm Mitigation Resources.